Legal Clinic attorney Amber Harding delivered the testimony below before the DC Council Committee on Human Services and Committee on Transportation and the Environment, at the Public Oversight Roundtable on June 25, 2018.

Want to know more? You can read Amber’s full testimony and attachments submitted to the Committees. You can also watch the hearing in its entirety, and follow along with this fact-checking piece published by Washington City Paper.

Good afternoon Chairwomen Nadeau and Cheh and Council members. My name is Amber Harding and I’m an attorney at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless. The Legal Clinic envisions – and since 1987 has worked towards – a just and inclusive community for all residents of the District of Columbia, where housing is a human right and where every individual and family has equal access to the resources they need to thrive.

Bowser Administration officials appear to have purposely misled the Council, the community and, most importantly, homeless families about whether the Wards 7 and 8 DC General replacement shelters would be ready this fall. These same officials have assured families that there will be enough shelter to meet the need when they close DC General this fall. These same officials have assured families that all the construction and demolition at DC General is being done competently and safely, without risking lead poisoning or other irreparable harm. How can families – or any of us – trust these assurances? This hearing presents an opportunity for the Council to figure out who knew what, and when, and the extent of their falsehoods. We ask the Council to demand the resignation of anyone who knew or should have known of the massive incompetence and delays and either did nothing about it, or engaged in the cover-up.

The timing of the replacement shelters coming online is critical, since many plans hinge on that. We want to be clear that our bottom line, though, remains unchanged by the timing of the construction—DC General must close, but not until all the replacement shelters are ready. That was, after all, the original plan that we all agreed was best for homeless families. (As Homeward DC states: “When all of the new units are delivered, we can close DC General.”) We also want to be clear that our position is still that no demolition should take place on the DC General campus until the families have moved out, and even then, the process must be done to the highest standard of safety for the sake of the women at Harriet Tubman and the men and women at the DC jail.

It is critical to have this roundtable today, both because this type of incompetence and dishonesty from government officials should not be tolerated, but also because the public needs the Council to shine some real transparency on the DC General closure plan. There are limited ways that the public can really know how the executive is performing, after all. We have the press, freedom of information requests, public meetings, and Council oversight. But what good are any of those avenues when the Bowser administration flagrantly lies, obfuscates and/or violates open government laws to avoid every attempt at checks and balances?

Perhaps it seems harsh that I am already characterizing the Bowser Administration’s statements as lies when they haven’t yet testified. Perhaps they were hopeful that they would work out the problems with the sub-contractor and indeed open the shelters on time. But there was no hedging, no qualifying. They did not give anyone any indication that the timeline might be drastically different, that they were struggling to work with a completely inexperienced company. They did not say “we hope” that the shelters will be on time or “we’re working towards” a fall delivery date. They made strong, assured statements, leaving no room for anyone to doubt or question or even help, and then they engaged in a pattern of withholding, of hiding, critical public information that could have pushed a wedge of sunlight in. People with no intent to lie do not speak to 20 people and a PR firm before giving a one sentence statement to the press. People with no intent to lie do not put up every obstacle to FOIA requests they can, lawful or not, including denying the Legal Clinic’s public interest fee waiver request and charging more than $1400 for a few documents and completely blacked out emails. They lied. Repeatedly. To all of us. Today we need to learn who knew it was a lie, and who decided this lie must be maintained.

My written testimony includes specific examples of the Administration’s lies to the press, to the public (including Wards 7 and 8 shelter advisory teams), to the Legal Clinic, and to the Council. I am happy to answer questions about any of those examples.

Here are some basic questions that I believe the Administration needs to answer today:

- Why was Z Modular chosen? Whose responsibility was it to vet the subcontractor? Was it really just a “flashy video” that convinced them to contract with them? Is that their normal business practice?

- What is the actual status of each replacement shelters? In addition to Wards 7 and 8, are there contracts in place for 3, 5 and 6? Has construction started on those sites or not?

- If, in order to get the Wards 7 and 8 shelters finished by October they have to work until 1AM six or seven days a week, what are the overtime costs for that? What are the tradeoffs in quality if workers are there for eighteen hour days? What is the impact on neighbors? What is the impact on the FY18 budget?

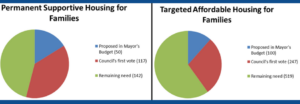

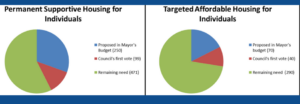

- What is the impact on the recently passed FY19 budget if there are significant delays in any of the shelters? On capital spending? On hotel costs? On contracts for replacement shelters and their operating costs?

- Who was part of the “entire executive leadership team” that Director Gillis briefed on the progress of the shelters?

- Who is ultimately responsible for the plan to close DC General and open its replacement shelters? The Director to End Homelessness, who apparently also knew that these two shelters were behind schedule? The Director of DHS? The Director of DGS? The City Administrator? The Deputy Mayor? Assuming any one of them claims to have known nothing about the problems with the sub-contractor, is ignorance a defense to responsibility for anyone charged with closing DC General responsibly?

###

What Can You Do?

- Get More Background

- “Life Inside D.C.’s Motel Homeless Shelters” Washington City Paper, June 28, 2018

- “Gleaming Posters for New Development, Construction, Dust: What It’s Like to Live at D.C. General Right Now” DCist, June 28, 2018

- High Turnover and Low Morale Among D.C. Workers Managing Homeless Shelter Construction Projects, Washington City Paper, June 25, 2018

- Fact-Checking the Council Roundtable on Homeless Shelter Delays, Washington City Paper, June 25, 2018

- Officials Will Investigate Reported Delays in the Ward 7 and 8 Homeless Shelters, Washington City Paper, June 21, 2018

- Documents Show Construction Debacle Jeopardizes Homeless Shelter Replacement Plan, Washington City Paper, June 15 2018

- Talk to DC Council:

- Councilmember Brianne Nadeau, (Ward 1) Chair of the DC Council Committee on Human Services, with oversight of the Department of Human Services: bnadeau@dccouncil.us

- Councilmember Mary Cheh, (Ward 3) Chair of the DC Council Committee on Transportation and the Environment, with oversight of the Department of General Services: mcheh@dccouncil.us

- Talk to the Mayor: Email Mayor Bowser (mayor@dc.gov). She needs to know that we all support closing DC General, but only if it is done in a way that centers and respects the health, safety, and stability of families who are homeless. Ask her to show you that commitment with actions, not words.